What are the causes?

The cerebrospinal fluid can be infected by a virus, a bacterium or a fungus.

Bacterial meningitis infections can be serious, and the species responsible for acute meningitis vary according to age. The human nasopharynx is the natural habitat of the bacterial species most often responsible for acute meningitis (H. influenzae, N. meningitidis and S. pneumoniae). Following a local, respiratory or ENT infection (tonsillitis, ear infection, sinusitis, etc.), bacteria can be found in the blood and may cross the blood-brain barrier to infect the cerebrospinal fluid, leading to swelling and inflammation of the meninges.

Fungal meningitis infections are less common but very serious. In France, they are monitored by the National Reference Center for Invasive Mycoses and Antifungals at the Institut Pasteur. Cryptococcus neoformans is the main fungus responsible for meningitis, and pigeon droppings are a reservoir. This yeast causes opportunistic infections, particularly in AIDS patients. Other fungi can also cause meningitis.

How does the disease spread?

The bacteria spread through respiratory droplets and respiratory or throat secretions. The bacteria are found in the throat and nose of the infected person, and close and prolonged contact between individuals is required for the disease to spread.

Other bacteria that can cause meningitis are group B streptococci, which often colonize the vagina and can be transmitted from mother to infant during childbirth.

What are the symptoms?

Meningococcal meningitis generally occurs in early childhood (most often in infants under the age of one) and in adolescents and young adults (aged 16 to 24).

The incubation period is generally 3 to 4 days but can last up to 10 days. Meningitis is characterized by an infectious syndrome (fever, severe headaches, vomiting) and a meningeal syndrome (stiff neck, drowsiness, confusion or even coma). In newborns and infants, these symptoms are less apparent and the high fever is sometimes accompanied by convulsions or vomiting. The appearance of a red skin rash (purpura) that gradually spreads (widespread purpura) is a marker of infection severity and can lead to septic shock, requiring antibiotic treatment and emergency hospitalization.

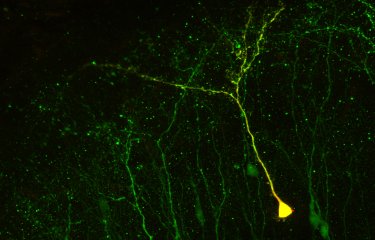

The most common complication of cerebrospinal meningitis is neurological damage, particularly deafness.

When bacteria infect the blood, the extremities of the body can become cold, muscle and joint pain can occur and breathing can speed up. Newborn infants can experience different symptoms – they may refuse to eat and become lethargic or inconsolable, and they may also develop a bulging fontanelle (the membrane-filled space between the bones of the skull).

Viral meningitis infections are generally mild in patients with no immune deficiency, and recovery is usually spontaneous – patients recover fully within a few days with no lasting effects.

How is infection diagnosed?

After a clinical examination, a lumbar puncture (removal of a sample of cerebrospinal fluid) is performed, together with a blood culture test to identify bacteria in the blood.

What treatments are available?

The severity and risk of rapid progression of meningococcal infections mean that antibiotic treatment must be prescribed as quickly as possible. Treatment is administered intravenously, usually for a period of 4 to 7 days. In industrialized countries, the first-line treatment is third-generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime and ceftriaxone). Surveillance of antibiotic resistance is therefore vital as it would be a huge blow in the fight against outbreaks in the "meningitis belt," the region of Sub-Saharan Africa from Senegal to Ethiopia which is particularly affected by meningococcal meningitis.

How can infection be prevented?

The best prevention is vaccination. Several effective vaccines are available for various types of meningococcus.

In France:

- Meningococcal C vaccination is mandatory for infants born after January 1, 2018. The vaccine is administered at 5 months, with a booster dose at 12 months. A catch-up vaccine may be administered in a single dose to people aged between 12 months and 24 years old.

- Meningococcal B vaccination has been recommended since April 2022. The vaccine schedule consists of two doses at 3 and 5 months, followed by a booster dose at 12 months. A booster dose every 5 years is also recommended for people at ongoing risk of exposure to meningococcal B infection.

See the details of the meningitis vaccine recommendations on the French Health Insurance website

In all cases of meningococcal infection, preventive antibiotic treatment or antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended for anyone in close contact with the patient to prevent transmission between individuals – rifampicin must be administered for two days. But there are contraindications (hypersensitivity, pregnancy, severe liver disease, alcoholism, etc.), and rifampicin resistance has been reported for rare meningococcal strains. In these cases, prevention is based on ceftriaxone administered by injection or ciprofloxacine taken orally, in a single dose.

In the case of serogroup A, C, Y or W meningococcal meningitis, prevention through vaccination complements the antibiotic prophylaxis introduced to protect individuals who have come into close and repeated contact with a patient (generally those living at the same address) and young children living in crowded group settings.

How many people are affected?

Newborn infants and young children are most at risk of developing the disease. Meningococcal infections affect 500,000 people every year worldwide, according to WHO figures.

In France, around 500 to 600 people are affected by severe meningococcal infection every year. Although the number of meningococcal infections fell during the COVID period, a significant "post-COVID" resurgence was observed in 2022-2023 (421 cases between January and September 2023).

New weapons to fight bacteria

March 2024