What are the causes?

Group A Streptococcus

The bacteria are mainly found in the throat and pharynx.

Group B Streptococcus

The main reservoir of Streptococcus agalactiae is the digestive tract, from where the bacteria may colonize the female genital tract, often on a sporadic basis.

How do the bacteria spread?

Group A Streptococcus

Group A Streptococcus (GAS), Streptococcus pyogenes, only spreads between humans through respiratory droplets and direct contact, for example via nasal secretions or skin lesions.

Group B Streptococcus

Neonatal infections are mostly linked with the inhalation and ingestion of vaginal secretions during childbirth. Mother-to-child transmission essentially occurs if the baby inhales or ingests infected amniotic fluid when the fetal membranes rupture or during delivery by passage through a GBS-colonized birth canal.

What are the symptoms?

Group A Streptococcus

The bacteria cause frequent benign, non-invasive infections, such as strep throat and impetigo. The most common symptoms are sore throat, fever, redness and swollen tonsils. But group A Streptococcus is also responsible for severe invasive infections, such as bacteremia (bacteria in the blood), necrotizing skin infections, puerperal infections (post-partum infections), pleurisy (a complication associated with lung inflammation) and meningitis, which may be associated with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome.

Group B Streptococcus

GBS infections in newborns may be divided into two types, depending on when they occur: Early-onset infections, 80% of which occur during the first 24 hours of the infant's life, and late-onset infections, which occur between the first week and the third month. Early-onset infections generally cause respiratory distress and bacteremia (in 89% of cases). Meningitis is a less common clinical presentation in early-onset forms (10-20% of cases). Late-onset neonatal infections are associated with bacteremia and meningitis in most cases.

Most invasive infections in pregnant women present as bacteremia, sometimes associated with intrauterine infections (infection of the placental tissue). Infection with group B Streptococcus outside the context of pregnancy and early infancy mainly gives rise to bacteremia, but cases of arthritis, endocarditis and meningitis have also been reported. Age and underlying medical conditions such as diabetes or cancer are risk factors.

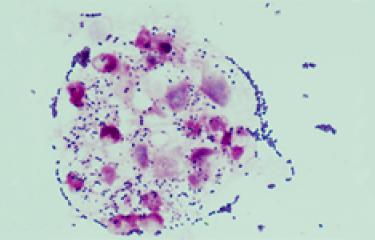

How is infection diagnosed?

An initial clinical examination is systematically performed. Streptococcal infections are generally diagnosed by a throat culture to identify the specific type of Streptococcus bacteria.

Pregnant women are screened for S. agalactiae (group B Streptococcus).

What treatments are available?

Antibiotics known as ß-lactams are currently the treatment of choice for streptococcal infections. For several years now there has been a rise in resistance to some classes of antibiotics.

There is no vaccine for group A Streptococcus infections.

Intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis is based on a ß-lactam (penicillin or amoxicillin) or a macrolide in the event of an allergy. In newborns, treatment mainly involves the intravenous administration of ß-lactam (amoxicillin), possibly in conjunction with another antibiotic (gentamicin) for the first 48 hours, over a period of 10 days to 3 weeks depending on the site of infection (meningitis, arthritis, etc.).

There is no vaccine for group B Streptococcus infections.

How can infection be prevented?

Close contacts of patients with an invasive S.pyrogenes are at greater risk of contracting a secondary infection than the rest of the community. Basic hygiene practices used to protect against seasonal viruses are therefore recommended, such as washing hands, wearing a mask and sneezing into the elbow.

In pregnant women, systematic screening for S. agalactiae is recommended between 34 and 38 weeks of amenorrhea.

How many people are affected?

There has been a significant rise in invasive GAS infections in industrialized countries, especially in Europe. In France, invasive infections have been on the rise since the 2000s.

GAS infections cause a variety of different conditions; the overall mortality rate is thought to be around 10%.

In France, around 500 cases of invasive neonatal infection are recorded each year, leading to between 30 and 60 deaths.

The transmission rate from mothers with GBS to newborns is 50% on average, and approximately 1 to 2% of newborns go on to develop an infection if antibiotic prophylaxis is not administered to women with GBS colonization during childbirth.

September 2024