What are the causes?

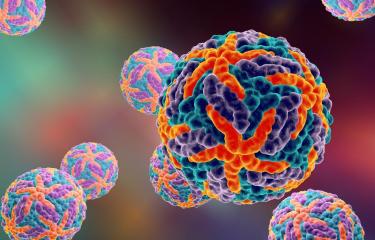

Dengue, like the West Nile and yellow fever viruses, is caused by an arbovirus (a virus transmitted by arthropods) belonging to the Flavivirus genus of the Flaviviridae family.

There are four distinct dengue virus serotypes: DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3 and DENV-4. Individuals infected by one of the serotypes acquire protective immunity against that serotype but not against the others. Consequently, infection with each of the four dengue serotypes may occur in a person’s lifetime. Subsequent infection with other serotypes increases the risk of developing severe, or hemorrhagic, dengue.

What are the symptoms?

Most people have mild or no symptoms.

‘Classic’ dengue is characterized by acute onset of high fever, often with headaches, nausea and vomiting, following an incubation period of 4 to 10 days. Symptoms persist for two to seven days, and the person’s health generally improves. Full recovery can take around two weeks. ‘Classic’ dengue, although highly debilitating, is not considered a severe disease.

For reasons that remain unclear, in some patients the clinical course may progress to ‘severe’ dengue fever. This usually occurs after the initial fever has subsided and is characterized by two severe forms.

- Dengue hemorrhagic fever: the hemorrhagic form accounts for around 1% of dengue cases worldwide. In addition to severe abdominal pain and persistent vomiting, associated symptoms include multiple hemorrhages, particularly in the gastrointestinal tract, skin and brain. Children aged under 15 years in particular may experience hypovolemic shock (a significant drop in blood volume). This is characterized by cold, clammy skin and an impalpable pulse – signs of circulatory failure, which may result in death if adequate perfusion is not re-established.

- Dengue shock syndrome. This lethal form is characterized by:

o circulatory collapse, i.e. an acute failure of circulatory function resulting in a drop in blood pressure, extreme tachycardia and pallor sometimes associated with cyanosis, etc.

o and multiple organ failure, i.e. rapid deterioration of one or more organs or viscera.

Individuals infected for a second time are at greater risk of developing severe dengue.

How does the virus spread?

It is transmitted to humans through the bites of female mosquitoes of the genus Aedes, mainly Aedes aegypti, but sometimes also the tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus). When a mosquito feeds on the blood of an infected person, the virus replicates in its intestine before entering the salivary glands. Under certain conditions, the mosquito becomes infectious within a few days and can then infect other people.

More rarely, the virus can be transmitted from a pregnant woman to her baby, or through transfusion or transplantation.

How is the disease diagnosed?

In all cases, rapid, accurate diagnosis is necessary to confirm the infection in order to support patient care and ensure that public health surveillance systems can sound the alarm and intensify efforts to combat the spread of the virus.

Diagnosis is based on:

- detection of the virus

Several strategies can be used, including: isolation of the virus by cell culture; a serological test to identify a specific antigen (NS1); an RT-PCR test to detect the viral genome.

- detection of antibodies in response to infection

Serological tests can detect IgM and IgG levels. IgM appears a few days after the onset of symptoms and persists for several weeks. IgG appears shortly after IgM and persists for life.

See the diagnostic approach recommended in France on the Santé publique France website (in French)

What treatments are available?

There is no specific treatment for dengue. Symptoms associated with the disease are treated with analgesics. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided, as they may increase the risk of bleeding.

How can infection be prevented?

Prevention relies mainly on vector control, i.e. fighting the mosquitoes that spread the virus, and personal protection measures: removing stagnant water, using repellents, wearing full-body clothing and using mosquito nets. Insecticides can also be used, but their widespread use can induce resistance in mosquito populations, making them less effective.

There is also a preventive vaccine, Dengvaxia®, administered in three doses six months apart, which is only available to certain individuals: those aged 9 to 45 years, previously infected with the virus and living in endemic areas.

Consult the dengue vaccination recommendations of the French National Authority for Health (in French)

How many people have been affected?

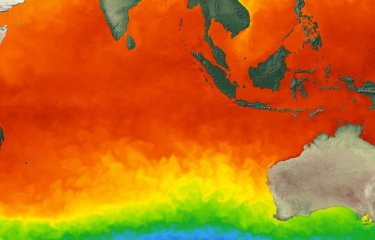

Dengue is considered a re-emerging disease. Between 2000 and 2019, the number of cases reported worldwide rose from 500,000 to 5.2 million. Although initially present in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, dengue is spreading to new geographical areas as a result of global warming, the global economy and the increase in international trade and travel. By 2010, dengue had spread to Europe and two indigenous cases were reported.

114 indigenous cases were recorded in mainland France in the period between 2010 and 2022.

By 2023, the mosquito vector was established in 71 French departments and the first case of indigenous dengue was confirmed in the Greater Paris region. (in French)

In the first half of 2023, WHO reported nearly 3 million cases and over 1,300 deaths in Latin America. There could be more than 4 million cases worldwide in 2023.

“The Geopolitics of the Mosquito” - Go further with our experts!

November 2023