Scientists at the Institut Pasteur and its International Network, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute (Cambridge, United Kingdom) and several international institutions have just published an exceptionally wide-ranging study tracing the history of the bacillus responsible for epidemic dysentery – one of the worst scourges to afflict humans throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. This vast scientific investigation has uncovered hitherto unknown links between the various outbreaks that have occurred through history. In particular, it reveals that the pathogen currently raging through Africa and Asia probably originated in Europe and was transmitted from one continent to another via migratory movements and military operations. It also charts the development of the pathogen’s inexorable resistance to antibiotics. This study is published in the journal Nature Microbiology on March 21.

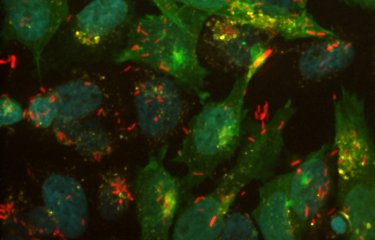

Colored image of Shigella, the agent of bacillary dysentery. © Institut Pasteur

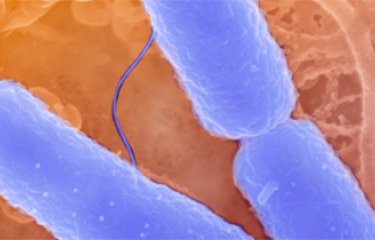

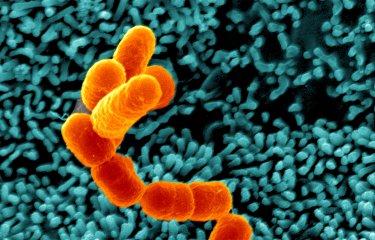

The agent of epidemic dysentery, the bacterium Shigella dysenteriae type 1, was isolated in Japan in 1897 by Dr Kyoshi Shiga during a massive epidemic of bloody diarrhea that caused 20,000 deaths over a six-month period. Since then, strains have been isolated the whole world over, but without any light being shed on the origin of the epidemics caused by them or the links between them.

To provide an understanding of this disease, a team of scientists led by François-Xavier Weill from the Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit at the Institut Pasteur and Nicholas Thomson from the Bacterial Genomics and Evolution group at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, have undertaken an unprecedented genomic study. Using new technologies for bacterial genome sequencing and bioinformatics, they analyzed more than 330 strains of Shigella dysenteriae type 1 isolated between 1915 – in soldiers taking part in the Dardanelles campaign – and 2011 and collected by 35 international institutes in 66 countries.

The study shows that, contrary to popular belief, the Shigella dysenteriae pathogen currently raging across Africa and Asia is most probably of European origin. Scientists consider that the common ancestor of the most ancestral strains circulating in Europe early in the 20th century existed as far back as the 1740s, and that it could have been responsible for the violent epidemics of bloody diarrhea described in Western and Northern Europe during the 18th and 19th centuries – well before the work of Louis Pasteur and studies in microbiology. These dysentery epidemics went on to kill over 200,000 people in France, mainly between 1738 and 1742 and in 1779, and 35,000 in Sweden between 1770 and 1775. In the 19th century, Ireland was also severely affected, during the great famine of 1846 to 1849, and the disease struck again in France during the Franco-Prussian War.

European expansion helped propagate the pathogen

By identifying different genetic lineages, the scientists were able to trace the path of the bacterium worldwide over time. In well under 20 years, between 1889 and 1903, S. dysenteriae started in Europe and spread from there to America, Africa and Asia. This dissemination was probably aided by population movements during European emigration to America as well as the colonization of territories in Africa and Asia. The whole process was also likely facilitated by steam navigation and the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869.

In the 20th century, the bacterium reappeared in Europe during the First World War, in particular during the Dardanelles campaign (1915-1916), where it was a significant factor in the defeat of the Allied troops. It was also identified in Central Europe during the Second World War, before dying out in Europe.

However, it continued to spread across Asia, Africa and Central America in the form of violent outbreaks. The Central American epidemic of 1969 to 1972 saw 500,000 cases. The outbreak in the Indian subcontinent (India and Bangladesh) subsequently became active throughout the 20th century and would prove to be the source of several epidemic waves that spread to Africa and South-East Asia.

In the 25 years between 1965 and 1990, 99% of strains developed antibiotic resistance. Since the first bacteria were isolated well before the use of antibiotics in humans, study of the collection has also placed a precise date on the appearance of the first antibiotic resistance, in Asia and America in the mid-1960s. The bacterium then acquired resistance genes against most classes of antibiotics, and since the 1990s less than 1% of bacterial strains have remained susceptible to antibiotics. Scientists consider it inevitable and a cause for concern that the Shiga bacillus circulating in the same regions as these resistance genes shall acquire resistance to the last-resort antibiotic classes. This pessimistic outlook may, however, be balanced against a reduction in infection since 2010, including in Southern Asia and Africa. Although the bacterium is no longer isolated during epidemic waves, it is still found during field studies, such as that carried out by Médecins Sans Frontières in diarrheal children in Niger in 2011. For Dr François-Xavier Weill, the Shiga bacillus is still circulating at a low level, and could be responsible for future epidemics if conditions should prove favorable – such as a large gathering of people without access to drinking water or treatment of human waste. He believes that this study highlights the need for an effective vaccine, which will be crucial for controlling this disease in the future in view of the reduced efficacy of antibiotics.

This study received funding from the Institut Pasteur, the Institut Pasteur International Network, InVS, IBEID laboratory of excellence, Le Roch Les Mousquetaires Foundation, and the Wellcome Trust.

Source

Global phylogeography and evolutionary history of Shigella dysenteriae type 1', Nature Microbiology, March 21, 2016.

Elisabeth Njamkepo (1)†, Nizar Fawal (1)†, Alicia Tran-Dien (1)†, Jane Hawkey (2,3,4), Nancy Strockbine (5), Claire Jenkins (6), Kaisar A. Talukder (7), Raymond Bercion (8,9), Konstantin Kuleshov (10), Renáta Kolínská (11), Julie E. Russell (12), Lidia Kaftyreva (13), Marie Accou-Demartin (1), Andreas Karas (14), Olivier Vandenberg (15,16), Alison E. Mather (17,18), Carl J. Mason (19), Andrew J. Thandavarayan Ramamurthy (20), Chantal Bizet (21), Andrzej Gamian (22), Isabelle Carle (1), Amy Gassama Sow (9), Christiane Bouchier (23), Astrid Louise Wester (24), Monique Lejay-Collin (1), Marie-Christine Fonkoua (25), Simon Le Hello (1), Martin J. Blaser (26), Cecilia Jernberg (27), Corinne Ruckly (1), Audrey Mérens (28), Anne-Laure Page (29), Martin Aslett (17), Peter Roggentin (30), Angelika Fruth (31), Erick Denamur (32), Malabi Venkatesan (33), Hervé Bercovier (34), Ladaporn Bodhidatta (19), Chien-Shun Chiou (35), Dominique Clermont (21), Bianca Colonna (36), Svetlana Egorova (13), Gururaja P. Pazhani (20), Analia V. Ezernitchi (37), Ghislaine Guigon (38), Simon R. Harris (17), Hidemasa Izumiya (39), Agnieszka Korzeniowska-Kowal (22), Anna Lutyńska (40), Malika Gouali (1), Francine Grimont (1), Céline Langendorf (29), Monika Marejková (41), Lorea A.M. Peterson (42), Guillermo Perez-Perez (26), Antoinette Ngandjio (25), Alexander Podkolzin (10), Erika Souche (43), Mariia Makarova (13), German A. Shipulin (10), Changyun Ye (44), Helena Žemličková (11,45), Mária Herpay (46), Patrick A. D. Grimont (1), Julian Parkhill (17), Philippe Sansonetti (47), Kathryn E. Holt (2,3), Sylvain Brisse (38,48,49), Nicholas R. Thomson (17,50) and François-Xavier Weill (1,17)*

(1) Institut Pasteur, Enteric Bacterial Pathogens Unit, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(2) Centre for Systems Genomics, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia.

(3) Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bio21 Molecular Science and Biotechnology Institute, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia.

(4) School of Agriculture and Veterinary Science, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3010, Australia.

(5) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Escherichia and Shigella Reference Unit, Atlanta, Georgia 30333, USA.

(6) Public Health England, Gastrointestinal Bacteria Reference Unit, Colindale NW9 5HT, UK.

(7) icddr,b, Enteric and Food Microbiology Laboratory, Dhaka 1212, Bangladesh.

(8) Institut Pasteur in Bangui, BP 923, Bangui, Central African Republic.

(9) Institut Pasteur in Dakar, BP 220, Dakar, Senegal.

(10) Federal Budget Institute of Science, Central Research Institute for Epidemiology, Moscow 111123, Russia.

(11) Czech National Collection of Type Cultures (CNCTC), National Institute of Public Health, Prague 10, Czech Republic.

(12) Public Health England, National Collection of Type Cultures, Porton Down SP4 0JG, UK.

(13) Pasteur Institute of St Petersburg, St Petersburg, 197101, Russia.

(14) Department of Medical Microbiology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4041, South Africa.

(15) Department of Microbiology, LHUB-ULB, Brussels University Hospital Laboratory, 1000 Brussels, Belgium.

(16) Environmental Health Research Centre, Public Health School, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 1070 Brussels, Belgium.

(17) Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Cambridge CB10 1SA, UK.

(18) Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB3 0ES, UK.

(19) Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences (AFRIMS), Bangkok 10400, Thailand.

(20) National Institute of Cholera and Enteric Diseases (NICED), Kolkata, West Bengal 700010, India.

(21) Institut Pasteur, Institut Pasteur Collection (CIP), 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(22) Polish Collection of Microorganisms, Institute of Immunology and Experimental Therapy, 53-114 Wroclaw, Poland.

(23) Institut Pasteur, Genomics Platform (PF1), 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(24) Department of Foodborne Infections, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Nydalen 0403, Oslo, Norway.

(25) Pasteur Centre in Cameroon, BP 1274, Yaoundé, Cameroon.

(26) Departments of Medicine and Microbiology, New York University Langone Medical Center, New York, New York 10016, USA.

(27) Public Health Agency of Sweden, 17182 Solna, Sweden.

(28) Biology Department and Infection Control Unit, Bégin Military Hospital, 94160 Saint-Mandé, France.

(29) Epicentre, 75011 Paris, France.

(30) Institut für Hygiene und Umwelt, 20539 Hamburg, Germany.

(31) Division of Enteropathogenic Bacteria and Legionella, Robert Koch Institut, 38855 Wernigerode, Germany.

(32) INSERM, IAME, UMR 1137, Univ. Paris Diderot, IAME, UMR 1137, Sorbonne Paris Cité, 75018 Paris, France.

(33) Bacterial Diseases Branch, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910, USA.

(34) Faculty of Medicine, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Jerusalem 91120, Israel.

(35) Center of Research and Diagnostics, Centers for Disease Control, Taichung 40855, Taiwan.

(36) Istituto Pasteur-Fondazione Cenci Bolognetti, Dipartimento di Biologia e Biotecnologie C Darwin, Sapienza Università di Roma, 00185, Rome, Italy.

(37) Central Laboratories, Ministry of Health, Jerusalem 91342, Israel.

(38) Institut Pasteur, Genotyping of Pathogens and Public Health Platform, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(39) Department of Bacteriology I, National Institute of Infectious Diseases, Tokyo, 162-8640, Japan.

(40) Department of Sera and Vaccines Evaluation, National Institute of Public Health–National Institute of Hygiene, 00-791 Warsaw, Poland.

(41) National Reference Laboratory for E. coli and Shigella, National Institute of Public Health, Prague 10, Czech Republic.

(42) National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3E 3R2, Canada.

(43) Institut Pasteur, Bioinformatics platform, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(44) State Key Laboratory of Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, Beijing 102206, China.

(45) Department of Clinical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, Charles University, 500 05, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic.

(46) Hungarian National Collection of Medical Bacteria, National Center for Epidemiology, H-1097 Budapest, Hungary.

(47) Institut Pasteur, Molecular Microbial Pathogenesis Unit, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(48) Institut Pasteur, Microbial Evolutionary Genomics Unit, 75724 Paris Cedex 15, France.

(49) CNRS, UMR 3525, 75015, Paris, France.

(50) London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London WC1E 7HT, UK.

†These authors contributed equally to this work.