Photonic BioImaging – high-resolution microscopy in the era of artificial intelligence

New advanced microscopy techniques open up numerous possibilities, such as observing the mechanisms of living systems to elucidate and combat diseases like cancer, HIV and brain tumors, and identifying molecules which can be used in the development of new drugs. But microscopy tools are extremely expensive. So in the 2000s, the Institut Pasteur decided to set up a series of technological platforms to centralize and pool these systems. The Photonic BioImaging platform, which specializes in optical microscopy, is constantly tackling new technological challenges. We take a closer look.

To give you a glimpse of the daily workings of laboratories and the activities of scientists, the Research Journal includes regular features on some of the Institut Pasteur's teams. When we decide to shine a light on a specific research unit, the questions tend to come thick and fast. The scientists also have their fair share of questions to grapple with every day. With these regular "lab reports", we take you behind the scenes to find out more about each individual's work, role and hopes for the future.

On the Institut Pasteur's Paris campus, the Photonic BioImaging (PBI) platform can be found on the first floor of the François Jacob building – a facility named after the Institut Pasteur scientist and 1965 Nobel Laureate in Medicine who, together with André Lwoff and Jacques Monod, paved the way for modern molecular biology.

When you enter the PBI, it looks like a fairly ordinary research laboratory – a large space with an assortment of double offices, lab benches filled with all manner of equipment, and smaller rooms containing computers. But appearances can be deceptive: in reality, the PBI is the technological nerve center of the Institut Pasteur.

The many technological platforms on the Institut Pasteur campus centralize the most expensive technologies so that scientists can come and use them as and when they need to advance their scientific projects. The role of the Photonic BioImaging platform goes beyond this "self-service" approach. The team's experts – mostly engineers and scientists – develop and customize these technologies to meet specific scientific needs, and they also provide training for other scientists on campus in using the systems. That is what their job is all about: training up others so that they can ultimately use the systems on their own. Their work is a subtle blend of cutting-edge innovation and technological skills transfer.

A technological engineering hub that meets research needs

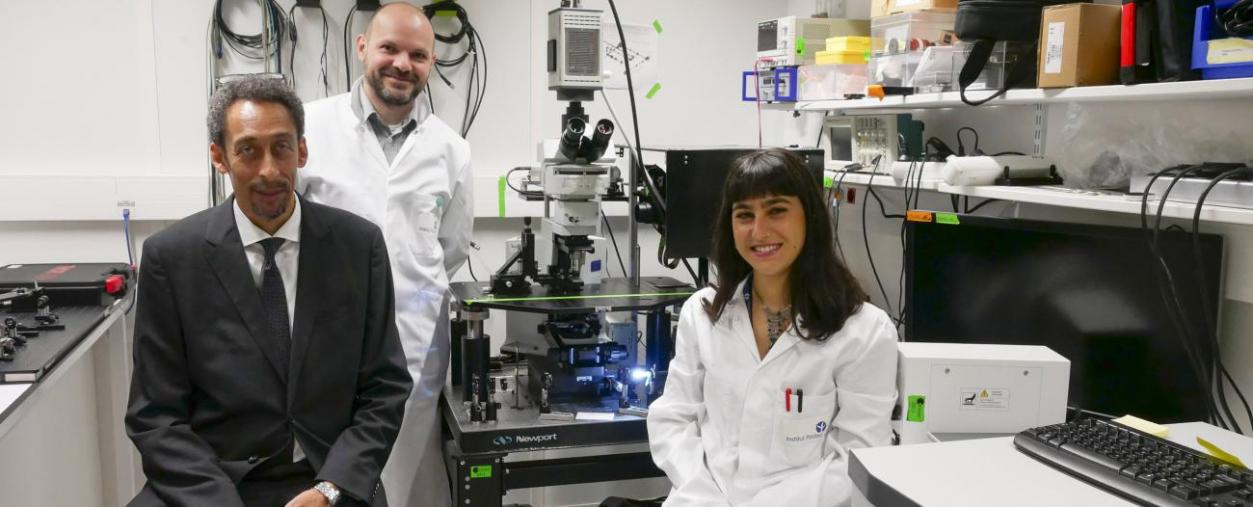

All the Institut Pasteur's platforms are part of the Center for Technological Resources and Research (C2RT), within the Department of Technology and Scientific Programs. Some of the platforms also carry out technological research activities; these are known as Technology and Service Units (UTechS) and are subject to the same experimentation, publication and funding requirements as the Institut Pasteur's other research units. So in practice, is there actually any difference between a scientist working for a unit and an engineer working for a platform? Spencer Shorte, Head of the PBI UTechS and, since 2018, Scientific Director of the Institut Pasteur Korea,* believes that "it's only in France that we make this distinction. In English-speaking countries, there is no difference. If you want to push back technological boundaries, you need to come up with theories and do everything you can to test them." Spencer Shorte joined the Institut Pasteur in 2001 as a platform head. In 2005 he set up an entirely novel structure, the "Imagopole", a hub for technological engineering at the Institut Pasteur that supported a wide range of discoveries in life sciences. The team was composed of experts in electron and optical microscopy and cytometry applied to basic and translational research. "At the time it was somewhat of a technological wilderness. It was vital to set up this sort of service center with state-of-the-art equipment. It was the only way to remain competitive in Europe," remembers Spencer. It was a transition that was not within easy reach, however. The platforms required considerable investment, with the recruitment of expert scientists and equipment that was as costly to maintain as to buy. That was the "price of research". But the added value of these platforms is such that, for the past 20 years, they have made a huge contribution to the Institut Pasteur's excellence. "Nowadays scientists can set up relatively small teams, safe in the knowledge that they will be able to draw on the Institut Pasteur's platforms and inherent multidisciplinary environment to carry out large-scale projects," emphasizes Spencer.

* The Institut Pasteur Korea is known for its use of imaging technologies in chemical and genome-wide phenotypic screening for drug discovery and basic research on infection and cancer.

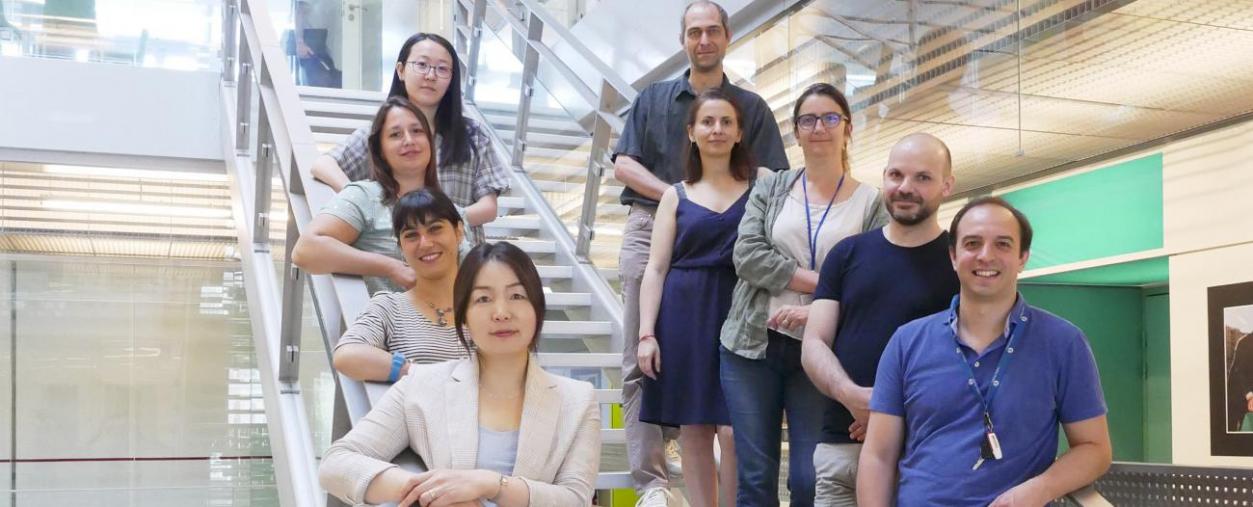

De gauche à droite :

Régis Tournebize, , Ioanna Theodorou, Julien Fernandes, Elric Esposito, Jong Eun Ihm, Adeline Mallet, Seoyoung Lee, Cidalia Da Agra, Nathalie Aulner.

Multidisciplinarity – the key to effective technological platforms

The need to adopt a cross-disciplinary approach is clear at all levels of the Photonic BioImaging platform. First and foremost, it is reflected in the nature of the team, coordinated by platform head Nathalie Aulner and composed of a dozen individuals with different but complementary personalities, backgrounds and expertise. Engineers, scientists, administrative staff and students all join forces to meet the recurring requirements of research. Most are there on a permanent basis, providing much-needed continuity. "There is a constancy, we know each other well. That really encourages synergy. In these professions there is not much turnover as experts are hard to find," explains assistant Cidalia Da Agra. Each member has a specialism, like Elric Esposito, the PBI's "research and development" engineer/physicist who customizes microscopes to meet specific needs, and Ioanna Theodorou, an engineer specializing in in vivo imaging who spends some of her time developing novel observation methods.

But they don't restrict themselves to their own area of expertise – they are all able to support and stand in for each other if needed, especially when it comes to leading training sessions for scientists. "We interact with each other – and with users – a great deal. We are involved in very different projects. This constant interaction is what cultivates our cross-disciplinary approach," reflects Ioanna. Cross-disciplinarity is a real hallmark of the services provided by the PBI.

We need to make sure our 300 annual users are satisfied with the service we provide, and constantly improve our practices to ensure we continue to respond to their requests as efficiently as possible

Nathalie Aulner's career began at an engineering school, where she studied biochemistry with a specialism in microbial genetics. She then turned to basic research and began a PhD, investigating chromosome structure during Drosophila development. Drosophila, a small vinegar fly, was also the focus of her post-doctoral fellowship in the United States. It was while she was in the States that Spencer Shorte asked her to join his team in Paris, in 2006. Nathalie Aulner joined the Institut Pasteur as an engineer at the Imagopole three years later, in 2009. Since she has taken over running the platform on an interim basis in the absence of Spencer, who recently became Scientific Director of the Institut Pasteur Korea, her time has been divided between managing activities, staff and equipment, and training users. "Since I arrived at the platform, my role has turned more to team management. Spencer was a wonderful mentor for me in that area. Now that I am managing the platform on a day-to-day basis, Spencer is able to focus his attention on large-scale European projects that make the best use of his considerable expertise."

Working in the platform as facilitators

When she is not managing the group, Nathalie continues with the activities she was involved in prior to taking up her temporary management role, which include training users in automated microscopy systems and scientific collaboration. "We study live pathogenic material and the interactions between pathogens and the cells they infect," she explains.

Another aim is to ensure that users are happy with the services provided by the platform, from the identification of needs to the provision of training and deliverables. "In 2007 we were awarded ISO 9001 quality certification. We need to make sure our 300 annual users are satisfied with the service we provide, and constantly improve our practices to ensure we continue to respond to their requests as efficiently as possible," she goes on. This quality certification clearly has an impact on efforts to secure funding to maintain and upgrade the systems she manages with Spencer.

For Nathalie Aulner, the primary role of the scientists and engineers working in the platform is as facilitators. They need to be committed to science, to apply their expertise to accelerate projects, and now also to adapt to the new possibilities afforded by artificial intelligence for microscopy.

Bioimage analysis supported by artificial intelligence

When scientists on the Institut Pasteur campus – roughly 300 each year who make up the majority of platform users – send a request to the PBI, they are asked to come and talk about it face to face. These discussions take place in "open desk" sessions. Then, in the platform, the team gets together to reflect on the best approach to deal with each request. By combining everyone's input, an effective response can usually be found. Once the request has been analyzed, the scientists are given training in how to use the chosen system. The aim is for them to become fully independent users with the ability to produce the images they need to test out a research theory or finalize a scientific publication themselves, without needing any help.

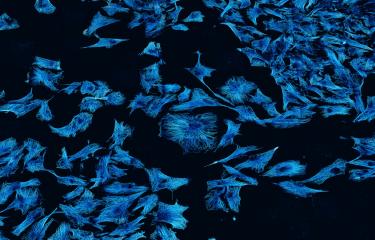

The end product is an image of a living system. Optical microscopy is the only technique that can be used to observe living material in cell cultures or experimental models. The PBI's work focuses on host-pathogen interactions and high-content imaging. It enables real-time observation of pathological phenomena, such as bacteria invading tissues or the movement of metastatic cells, through the routine use of fluorescent agents to mark cells, bacteria and viruses and track their movements through the body. The next stage is to analyze the images obtained. While the Photonic BioImaging platform may sometimes offer an interpretation of the images, scientists often turn to the Image Analysis Hub, led by Jean-Yves Tinevez, or the bioinformatics teams on campus. "We are increasingly finding that what is produced by the platform can no longer be processed or analyzed by humans. Artificial intelligence has become an absolute necessity over the past few years," explains Nathalie Aulner. The main hurdle for technological innovation is devising artificial intelligence applications to compile and analyze biological images that are being produced in ever larger quantities.

"We are on the cusp of unprecedented technological discoveries using artificial intelligence to analyze and process data," explains Spencer Shorte. The installation of the Titan Krios™ ultra-high-resolution cryo-electron microscope at the Institut Pasteur in July 2018 clearly illustrates this prospect. The state-of-the-art microscope, which offers atomic level resolution (in the range of a few tenths of a nanometer), is capable of observing up to 12 samples at the same time and collecting images over several days. It is vital for big data analysis to keep up with the dramatic technological progress in observation systems.

Combining different observation techniques

Every technology has its limits. Beyond a certain resolution, optical microscopy becomes ineffective and offers just one viewpoint among many. "It's the old "triangle of frustration": resolution can only be obtained to the detriment of speed and sensitivity; sensitivity can only be obtained to the detriment of spatial and temporal resolution; and speed can only be obtained to the detriment of spatial resolution and sensitivity," explains Nathalie Aulner with a wry smile. This is why scientists often combine a variety of observation techniques for the same project, so that they can approach the question from several angles. "Complex projects sometimes require a joint approach involving both optical and electron microscopy. In these cases, we deal with requests in conjunction with the PBI. Interdisciplinary cooperation between the various platforms is vital," explains Adeline Mallet, a research engineer in the Ultrastructural BioImaging Unit which provides support in electron microscopy. Inter-platform collaboration has always been a hallmark of the Institut Pasteur's research, echoing its broader interdisciplinarity. With expertise ranging from mass spectrometry to crystallography and molecular biophysics, a cross-disciplinary approach can boost effectiveness.

A service-oriented mindset – vital for working in a platform environment

The overriding strength of the Institut Pasteur's platforms is undoubtedly their service-oriented approach. "We leave our egos at the door – our aim is to find relevant and innovative solutions to the problems encountered by scientists," explains Nathalie Aulner.

"You need to be sociable, to enjoy helping others and facilitating their task. Engineers working for platforms tend to have more of a behind-the-scenes role than those in research units. They are often there to provide continuity in teams with high levels of diversity. Those who are only interested in their own work will find it hard being part of a platform," reflects Adeline Mallet. Recognition is a key issue when it comes to crediting contributions to publications. For while the ultimate aim of the Institut Pasteur's platforms is to advance research, they still have the same imperatives as any other research unit.

Publishing is vital for progress in research.

Cidalia Da Agra, assistant

From 2007 to 2015, Cidalia Da Agra tried her hand at various assistant jobs: firstly at a local radio station in Loir-et-Cher, then in the press relations and crisis communication unit at TBWA in Boulogne-Billancourt. In 2014, she found herself working as an assistant in the Prime Minister's Communication and Press Department – a job that was very isolated, requiring a "silo mentality" and offering no flexibility. "Although I learned a lot from my work in communications, there was something missing," she says.

She joined the Institut Pasteur in June 2015, after applying for a vacancy on pasteur.fr. Cidalia Da Agra became an assistant in the Malaria Parasite Biology and Vaccines Unit led by Chetan Chitnis, and was also affiliated with the CEPIA, a technological platform specializing in the production and infection of Anopheles. She was soon asked to choose between working for a unit or a platform. After opting for the latter, she became the assistant for the Photonic BioImaging (PBI), Ultrastructural BioImaging (UBI) and Image Analysis Hub platforms.

As well as general secretarial tasks (correspondence, appointments, meetings, etc.), her day-to-day activities involve helping to lighten the workload of her colleagues and freeing them up from administrative burdens to enable them to focus on their expert areas. In other words, she's a facilitator. And Cidalia Da Agra adapts seamlessly to the ever-changing configuration of her teams. "The success of my work depends more on chats at the coffee machine than phone calls or meetings. I need to be proactive, to go out of my way to make contact with people. There's certainly no silo mentality here." She attends the weekly organizational meetings every Monday, where the team discusses requests from scientists and also health and safety and the quality system for ISO 9001 certification, awarded to the PBI by French standards agency AFNOR, which monitors its application via audits. Cidalia is also in regular contact with her peers – every two weeks she meets the other assistants in the Center for Technology Resources and Research (C2RT) to share both positive experiences and any difficulties encountered in the course of her work.

She loves being at the Institut Pasteur: "I am very happy to work here. I feel proud to work for such a diverse, multidisciplinary institute, even if the slow procedures can sometimes be frustrating. My aim is to help people and offer them immediate solutions." She is pleased to have the opportunity to serve others.

Elric Esposito, research engineer

The era when scientists could handle complex microscopes without the help of engineers dates back some 15 years – around the time that Elric Esposito was beginning his physics studies in the United Kingdom after obtaining a DUT university diploma in Marseille. Following his MSc in Laser Physics, he worked for three years in industry in Scotland as a laser systems engineer, before leaving his job to begin a PhD. In 2010, he returned to France and embarked on two successive post-doctoral fellowships. "I wouldn't describe myself as a biologist. My professional experience since coming back to France has given me an understanding of biology and neuroscience, but my background is in physics: controlling and manipulating light and studying its interactions with tissues," observes Elric.

In September 2018, Spencer Shorte was looking for a new staff member to deal with research and development tasks for the Photonic BioImaging platform. The aim was to offer as wide a range of technological methods as possible to provide effective solutions for the ever growing and pressing needs of scientists. "It fitted my profile perfectly," enthuses Elric Esposito, who joined the Institut Pasteur for this position. His task was to apply his expertise to manufacturing hardware systems, particularly by recycling and customizing equipment that had become obsolete. Recycling offers a host of advantages: financial, since acquiring new technologies is extremely expensive; environmental, since this type of waste is not easy to dispose of; and also strategic, since Elric is able to make improvements to standard microscopes to meet highly specific needs on campus. This "tuning" can also be useful for manufacturers, who sometimes adapt their offerings based on this type of customer feedback.

Elric's time is divided equally between providing services – user training – and development. He interacts with suppliers and also with research units to promote new systems acquired by the platform for general use by scientists on campus. His technical expertise is in high demand whenever a microscope is being purchased. Although he only arrived at the Institut Pasteur recently, he has already settled into his role, and he particularly appreciates the diversity of projects he gets to work on. "I like being able to offer a whole range of technologies to find solutions for the problems faced by scientists. Passing on knowledge is also a rewarding experience. The Institut Pasteur's reputation and the specific issues at stake mean that manufacturers seem to be more interested and attentive when it comes to possible innovations," he explains. And that is clearly a motivating factor for someone who loves a challenge.

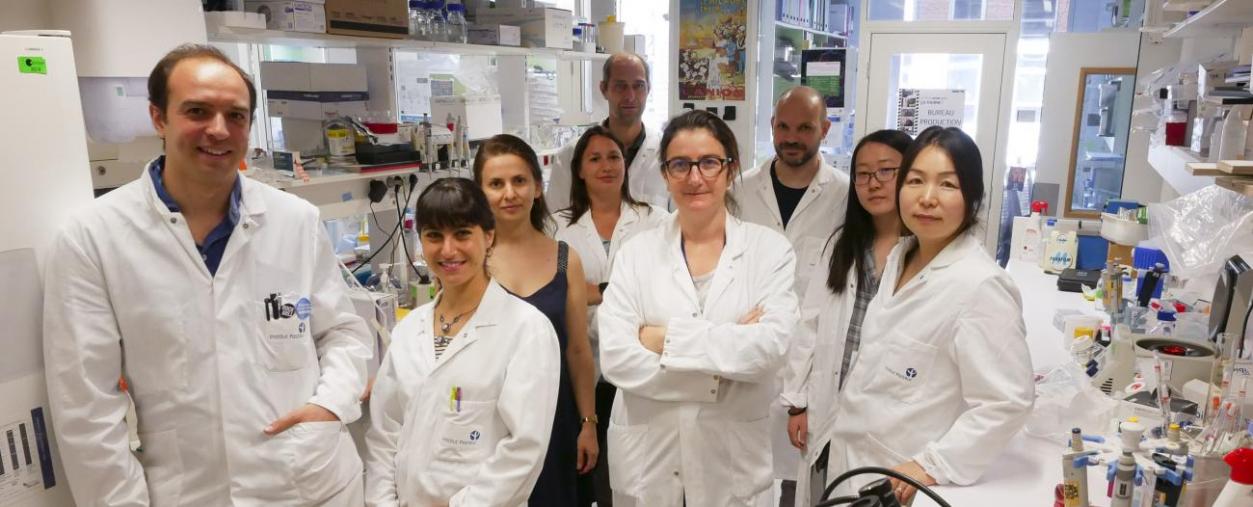

Adeline Mallet, engineer in the Ultrastructural BioImaging platform

Since electron microscopy cannot be used to observe living systems, the Ultrastructural BioImaging platform works regularly with the Photonic BioImaging platform. Adeline Mallet began her career at the Institut Pasteur at the tender age of 21, immediately after finishing her degree in Chemical and Pharmaceutical Industries. As a senior technician in the Ultrastructural BioImaging (UBI) platform led by Jacomina Krijnse Locker, she decided to develop her expertise by completing further studies in the highly targeted field of Platform Engineering at Paris Diderot University. In 2017, by then an engineer, she continued her career development by starting a PhD, which she is finishing this year. "I am a perfect example of internal career development. It's rare to find an institute that would encourage me to embark on a PhD while continuing my work as an engineer." To cap it all, Adeline Mallet also teaches Bachelor and Master students outside the Institut Pasteur. It is the constant curiosity demonstrated by these experts, as well as their often varied career paths, that enables the platforms to address multidisciplinary scientific issues so effectively.

Adeline is in a team of 14 people. She specializes in scanning microscopy, especially 3D microscopy. She assembles images of cells collected via state-of-the-art systems that combine surface morphology and intracellular information at nanoscale. As well as producing images for scientists, the platform also works with hospitals. "We currently work closely with the Pathological Anatomy and Cytology Department at Necker-Enfants Malades/AP-HP Hospital. Physicians and technicians work on our systems, especially for diagnostic purposes."

The Ultrastructural BioImaging platform is associated with a UTechS research unit. "This twofold approach is vital: we can draw on research projects to develop new methods, and scientists in the platform can find answers to their biological questions by using our systems. It's a great two-way dialog," explains Adeline.

The engineer believes that a successful career within the platform depends on sociability and availability. "You need to like helping people. Our role is a different type of engineer from those who work in laboratories." If a microscope breaks, Adeline has to put aside her thesis and her lesson preparation and set to work immediately to find a solution, so that the users can carry on with their research. Availability and a customer-oriented mindset – that's what it's all about.