With 82 million people currently infected in Africa, the hepatitis B virus represents a major health threat. Early treatment can considerably reduce the risk of complications associated with the disease. In a recent analysis, scientists challenged the suitability of the diagnostic tests used in sub-Saharan Africa and called for more optimized treatment for local populations.

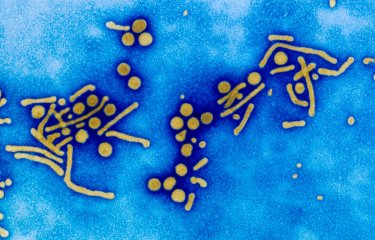

Hepatitis is a liver inflammation caused by toxic substances or viruses. There are currently five hepatitis viruses, including hepatitis B virus (HBV), which is particularly widespread among the world's population. It is estimated that 2 billion people have been infected with the virus and that 316 million currently live with chronic infection and are at high risk of developing severe liver disease. Most patients are infected at birth or during childhood, and major efforts have been made in recent years to treat HBV-positive pregnant women and to develop an effective vaccine strategy for newborn infants.

Despite these endeavors, HBV remains endemic in Africa, where around 82 million people are chronic carriers of the virus, most without being aware of it. Although HBV infection does not necessarily lead to pathological outcomes, it can result in severe complications and even cause liver cancer. Early therapeutic treatment can significantly reduce this risk. Current international guidelines recommend the administration of treatment for patients who develop cirrhosis and those with a high viral load and significant liver fibrosis. In high-income countries, liver fibrosis is generally assessed by biopsy or medical imaging techniques, but these diagnostic tools are rarely available in low-income countries.

Diagnostic tests poorly suited to sub-Saharan populations

Since 2015, in view of the difficulties in accessing these techniques, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended the use of low-cost laboratory tests for early diagnosis of at-risk individuals. These tests detect a specific biomarker, the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index (APRI). But are these recommendations appropriate for the African population? Following a vast collaborative study coordinated by the Institut Pasteur, the University of Oslo, the University of Liverpool and Imperial College London, scientists in the HEPSANET consortium argue that they are not. To reach this conclusion, the scientists analyzed the biomedical data of more than 3,500 chronic HBV carriers undergoing treatment at 12 healthcare facilities in eight African countries. The results showed that the APRI test, developed for Caucasian and Asian populations, has an inappropriately high threshold value for sub-Saharan populations, preventing reliable diagnosis. "We propose lowering the treatment decision threshold of the APRI biomarker for African patients and we call for hepatitis B guidelines that are better suited to the African context," explains Yusuke Shimakawa, a scientist in the Epidemiology of Emerging Diseases Unit.

Based on this study, the HEPSANET group is advocating for better care for the millions of patients infected with hepatitis B virus in Africa. Biological tests that are better suited to the sub-Saharan African population would increase the chances of reaching the target set by WHO of eliminating viral hepatitis as a public health threat by 2030. It is estimated that approximately a million people worldwide currently die of viral hepatitis each year.

Source:

Systematic review and individual-patient-data meta-analysis of non-invasive fibrosis markers for chronic hepatitis B in Africa, Nature communications, January 3, 2023

Asgeir Johannessen 1,2,23, Alexander J. Stockdale 3,4,23, Marc Y. R. Henrion 4,5,23, EdithOkeke6, Moussa Seydi7, Gilles Wandeler8, Mark Sonderup9, C. Wendy Spearman9, Michael Vinikoor10,11, Edford Sinkala10, Hailemichael Desalegn1,12, Fatou Fall13, Nicholas Riches5, Pantong Davwar6, Mary Duguru6, Tongai Maponga14, Jantjie Taljaard15, Philippa C. Matthews16,17,18, Monique Andersson14,16, Souleyman Mboup19, Roger Sombie20, Yusuke Shimakawa21,24 & Maud Lemoine22,24

1Department of Infectious Diseases, Vestfold Hospital, Tønsberg, Norway.

2Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway.

3Department of Clinical Infection, Microbiology and Immunology, Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecological Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK.

4Malawi-Liverpool-Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Programme, Blantyre, Malawi.

5Department of Clinical Sciences, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, Liverpool, UK.

6Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Jos, Jos, Nigeria.

7Service de Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales, Centre Regional de Recherche et de Formation, Centre Hospitalier National Universitaire de Fann, Dakar, Senegal.

8Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Bern, Bern, Switzerland.

9Division of Hepatology, Department of Medicine, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Cape Town, Cape Town, South Africa.

10Department of Internal Medicine, University of Zambia, Lusaka, Zambia.

11University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, USA.

12Medical Department, St. Paul’s Hospital Millennium Medical College, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

13Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Hôpital Principal de Dakar, Dakar, Senegal.

14Division of Medical Virology, Stellenbosch University Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Cape Town, South Africa.

15Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Tygerberg Hospital and Stellenbosch University, Cape Town, South Africa.

16Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK.

17The Francis Crick Institute, London, UK.

18University College London, London, UK.

19The Institute for Health Research, Epidemiological Surveillance and Training (IRESSEF), Dakar, Senegal.

20Yalgado Ouédraogo University Hospital Center, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

21Epidemiology of Emerging Diseases Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

22Department of Metabolism, Digestion and Reproduction, Division of Digestive Diseases, Hepatology section, Imperial College London, London, UK.

23These authors contributed equally: Asgeir Johannessen, Alexander J. Stockdale, Marc Y. R. Henrion.

24These authors jointly supervised this work: Yusuke Shimakawa, Maud Lemoine.