Discovery of a cellular mechanism involved in abnormal placental development during some high-risk pregnancies.

High-risk pregnancies occur frequently and may be caused by various factors. It is estimated that 10 to 20% of pregnant women miscarry during their first trimester of pregnancy. Slow fetal growth may also arise as a result of maternal infection with certain microbes, parasites or viruses (such as toxoplasmosis or infection with rubella virus, cytomegalovirus, herpes or Zika) or because of genetic or autoimmune diseases. Teams from the Institut Pasteur, the CNRS, Inserm, Necker-Enfants Malades Hospital (AP-HP) and Université de Paris have identified a new cellular mechanism that alters placental development, potentially causing serious complications during pregnancy. The mechanism is linked with the production of interferon, a molecule produced in response to infection, especially viral infection. The findings are published in Science on July 11, 2019.

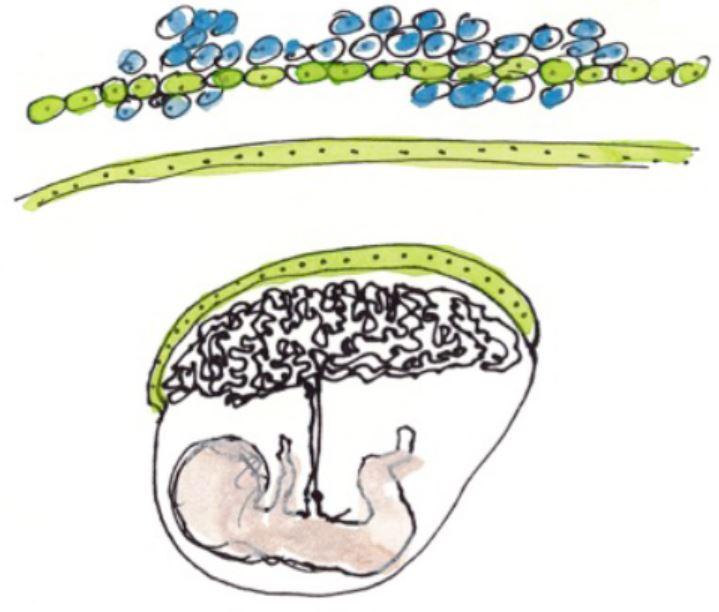

Artist's representation of cells and placenta © Fabrice Hyber – Organoïde-Institut Pasteur

The placenta is both a surface for exchange and a barrier between mother and fetus – it delivers nutrients needed for fetal growth, produces hormones and protects the fetus from microbes and the maternal immune system. The external layer of the placenta, known as the syncytiotrophoblast, is composed of cells which fuse together, forming giant cells that are optimized for the placenta's barrier and exchange functions. Cell fusion is mediated by a protein known as syncytin. If the syncytiotrophoblast fails to form correctly, it can cause placental insufficiency and hinder fetal development. An abnormal syncytiotrophoblast can be observed in conditions such as slow intrauterine growth, the lupus and in women whose fetus has Down syndrome.

Interferon is a substance produced by immune cells during infection to combat viruses and other intracellular microbes. High levels of interferon are observed in autoimmune or inflammatory diseases such as lupus, and also in some infections. In this study, the scientists demonstrated that interferon is responsible for placental abnormality and that it acts by preventing syncytiotrophoblast formation. Specifically, interferon induces the production of a family of cellular proteins known as IFITMs (interferon-induced transmembrane proteins), which block the fusion activity of syncytin.

IFITM proteins are beneficial since they prevent viral fusion with cellular membrane, thereby stopping viruses from entering and multiplying within cells. The scientists used experimental models and human cells to demonstrate that this beneficial effect can nevertheless be harmful if IFITM proteins are produced in an important level in the placenta.

"Identifying the role of IFITMs gives us a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in placental development and how it may be disrupted during infections and other diseases," comments Olivier Schwartz, Head of the Virus and Immunity Unit at the Institut Pasteur and joint last author of the paper. The scientists want to investigate whether placental pathologies of unknown etiology, such as some early spontaneous abortions and occurrences of preeclampsia, also involve IFITM proteins. In the longer term, blocking the effects of IFITMs could represent a new therapeutic strategy to prevent interferon-related placental abnormality.

In addition to the institutions mentioned above, this research was funded by the ANRS, Sidaction, the French Vaccine Research Institute (VRI), LabEx IBEID and the European Research Council (ERC).

Source

IFITM proteins inhibit placental syncytiotrophoblast formation and promote fetal demise, Science, 11 juillet 2019

Julian Buchrieser1,2*†, Séverine A. Degrelle3,4,5*, Thérèse Couderc6,7*, Quentin Nevers1,2*, Olivier Disson6,7, Caroline Manet8,9, Daniel A. Donahue1,2, Françoise Porrot1,2, Kenzo-Hugo Hillion10, Emeline Perthame10, Marlene V. Arroyo1,2,11, Sylvie Souquere12, Katinka Ruigrok2,13, Anne Dupressoir14,15, Thierry Heidmann14,15, Xavier Montagutelli8, Thierry Fournier3,4‡, Marc Lecuit6,7,16‡, Olivier Schwartz1,2,17†‡

1 Virus and Immunity Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France.

2 CNRS-UMR3569, Paris, France.

3 INSERM, UMR-S1139, Faculté de Pharmacie de Paris, Paris, France

4 Université Paris Descartes, Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris, France

5 Inovarion, Paris, France

6 Biology of Infection Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France

7 Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale U1117, Paris, France

8 Mouse Genetics Laboratory, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France

9 AgroParisTech, Paris, France

10 Bioinformatics and Biostatistics Hub – C3BI, Institut Pasteur, USR 3756 IP CNRS – Paris, France

11 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics and Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Columbia University, New York, NY 10032, USA

12 Plateforme de Microscopie Electronique Cellulaire, UMS AMMICA, Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France

13 Structural Virology Unit, Institut Pasteur, Paris, France

14 Unité Physiologie et Pathologie Moléculaires des Rétrovirus Endogènes et Infectieux, Hôpital Gustave Roussy, Villejuif, France

15 UMR 9196, Université Paris-Sud, Orsay, France

16 Université de Paris, Department of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine, Necker-Enfants Malades University Hospital, APHP, Institut Imagine, Paris, France

17 Vaccine Research Institute, Créteil, France.

* These authors contributed equally to this work.

‡ These authors contributed equally to this work.

† Corresponding author