Updated - September 2025

Legionnaires' disease is named after an outbreak that occurred in 1976 at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia, where 29 of the 182 delegates who contracted the disease died. It was later discovered that a previously unknown bacterium, Legionella pneumophila, had spread via the air conditioning system in their hotel. Several outbreaks of Legionnaires' disease have since been described in North America, Asia and Europe.

The recent emergence of the disease can be explained by the affinity of Legionella bacteria for modern water supply systems such as domestic hot water networks, cooling towers, spa pools and hot tubs, as well as air conditioning systems.

What are the causes?

Legionella bacteria are part of the aquatic microbial flora and are common in warm fresh water environments.

The genus Legionella comprises around 60 species, each representing dozens of serogroups. But the species Legionella pneumophila alone is responsible for more than 90% of cases of Legionnaires' disease diagnosed by culture, and more than 85% of cases are caused by isolates from serogroup 1.

The main causes of contamination are contaminated fresh water and air conditioning systems.

The bacteria multiply in microorganisms in water at temperatures between 15° and 50°C (often in showers, hot tubs and cooling towers).

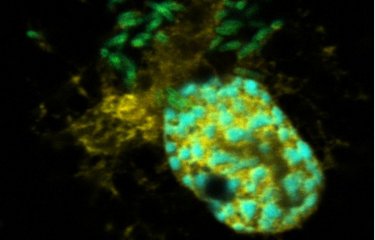

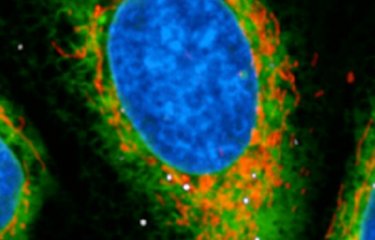

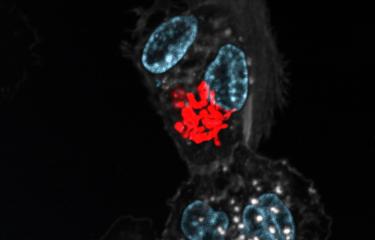

They can also multiply in protozoa found in fresh water, for example certain amoebae. When the amoebae die, the bacteria spread through the water and are ingested by a new host (a cell), enabling new cycles of multiplication.

The flooding and heavy rainfall caused by climate change facilitates the spread of Legionella bacteria.

Legionellae are intracellular bacteria but they can survive outside cells. The presence in water systems of organic deposits and other microorganisms, as well as iron, zinc and aluminum, encourages bacterial growth. The bacteria are resistant to heat and can therefore be found at the bottom of hot water tanks.

What are the symptoms?

When Legionella bacteria do not infect the lungs, they cause flu-like systems (fever, headache and muscle aches) which clear up after a few days. This is known as Pontiac fever.

The pulmonary form of legionellosis, Legionnaires' disease, is much more serious.

After an incubation period of 2 to 10 days, patients experience a pneumonia-like illness with acute pulmonary infection. The first symptoms resemble flu and include fever and a dry cough. There can be a general feeling of fatigue and a loss of appetite. Some patients may develop abdominal pain (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea) and neurological symptoms (from confusion and impaired consciousness to coma), as well as muscle pain. Symptoms may also include coughing up blood. In the absence of treatment, the disease generally gets worse over the first week. It can lead to irreversible respiratory failure and trigger acute kidney failure, both of which often prove fatal.

How does the disease spread?

One transmission route in humans is the inhalation of contaminated aerosols (water droplets suspended in the air) from aquatic environments. After inhalation, the bacteria can reach the pulmonary alveoli. They invade immune cells known as macrophages and ultimately destroy them. People can also contract the disease by aspiration of contaminated water.

Some specific cases are worth mentioning:

- newborn babies born in birthing pools;

- also patients in hospitals: an exceptional case of an immunocompromised patient (very fragile health) was observed in a hospital, infected via contaminated water / ice cubes (for example, ice machines can be a source of Legionella and should not be used by highly susceptible patients - source: WHO).

People with Legionnaires' disease are not contagious.

Only one case of human-to-human transmission has been reported to date. The case involved very close proximity between the two people in a confined space for a long time.

How is infection diagnosed?

Legionnaires' disease is diagnosed by clinical examination, taking into account the symptoms, context and risks to which the person may have been exposed. The diagnosis is then confirmed by a urine test that detects components of the outer membrane of Legionella.

Other diagnostic methods involve detecting Legionella in clinical samples (including via PCR), observing an increase in antibody titers in a urine sample or identifying the presence of antigens.

What treatments are available?

There is currently no vaccine for Legionnaires' disease. The bacteria responsible are naturally resistant to the types of penicillin usually used to treat lung conditions, but they can be effectively treated with other antibiotics such as macrolides (azithromycin or erythromycin), fluoroquinolones or rifampicin, if prescribed early enough. Rifampicin should not be taken on its own. These treatments are only effective if taken early enough in the development of the disease.

How can the disease be prevented?

Action needs to be taken to prevent the proliferation of Legionella. This includes:

- maintaining and cleaning fresh water systems and air conditioning systems

- applying physical measures (adjusting temperatures) and chemical measures (biocides)

- preventing aerosol emissions

- reducing stagnant water

Doctors must be on their guard to detect cases of Legionnaires' disease.

How many people are affected?

In France, between 1,600 and 2,000 new cases are reported each year, but these figures are likely to be lower than the real number of cases as the disease is difficult to diagnose. Legionnaires' disease is more common in over-50s and in men; other risk factors are smoking, diabetes, cancer, blood disease, and treatment with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants. According to WHO figures, 75 to 80% of reported cases are in people over the age of 50, and 60 to 70% are in men.

There are many more cases worldwide, but Legionnaires' disease is not easy to diagnose, and although it is a notifiable disease in France this is not the case in all countries.

September 2023

An example of a recent outbreak in FranceImproved surveillance has led to more effective detection of clustered outbreaks, and since 1998 several outbreaks linked to cooling towers have been identified. This was the case for the outbreak that occurred in winter 2003 in the Pas-de-Calais area, the largest observed in France to date in terms of both the number of cases (nearly 90 recorded cases and 17 deaths) and the size of the affected area – cases of infection were found around 10 kilometers away from the identified source of the outbreak. This incident highlighted how difficult it is to control the spread of Legionella pneumophila outbreaks because for the first time the industrial source needed to be shut down for full decontamination on two occasions, a month apart, to curb the outbreak. |