Scientists from the Institut Pasteur have demonstrated in rodents that, contrary to long-held belief, the malaria parasite is able to develop and produce infectious forms not only in the liver but also in the skin. This discovery proves that the skin is not merely a transitional site for the parasites on their way to the liver, but a site where the parasites can actually develop and even persist and where a protective immune reaction might be established. This means that it is possible to study and monitor the development of this immune response in the skin, which could help scientists analyze the efficacy of different vaccine strategies.

Press release

Paris, ocotober 5, 2010

The malaria parasite is transmitted to humans by the Anopheles mosquito and undergoes a complex maturation cycle in the host organism, particularly in the liver and then the blood, leading to the terrible disease which kills between one and three million people worldwide each year.

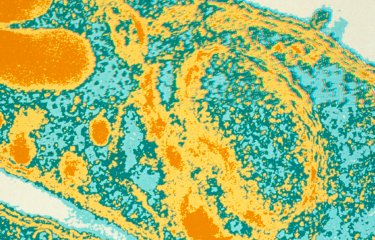

The scientific community had previously believed that after injection into the skin by the mosquito, the parasites quickly traveled to the liver, which was thought to be the only site in the organism where they would undergo the vital process of transformation into parasites capable of infecting red blood cells. Researchers from the Institut Pasteur’s Malaria Biology and Genetics Unit, directed by Robert Ménard, have recently disproved this theory. Using laboratory-developed in vivo real-time imaging techniques , they monitored the progress of parasites injected into the skin of mice and observed that 50% of them remained there. Ten percent of the parasites even followed their cycle for development into infectious form in the dermis, the epidermis and the hair follicles, without entering the liver at all.

The team also observed that the parasite, in association with the hair follicle, could persist in the organism on a long-term basis, i.e. for several weeks. Does this imply slower parasitic development, or does it instead correspond to a kind of persistence in a “dormant” state, as seen for example in Plasmodium vivax, one of the malaria parasites that infects humans? Although the researchers have not yet been able to find an answer to this question, it is intriguing to note that persistence occurs in the hair follicle, one of the few sites in the organism that the immune system cannot access. These dormant parasites might explain some cases of resurgence of the disease long after initial infection. Institut Pasteur scientists are already working to try to understand this phenomenon.

As well as identifying a secondary niche where the parasite may produce infectious forms and even persist, this research has considerable immunological implications. It has been known for some years that the lymph node draining the bite site is essential for building up protection against the disease. The current study demonstrates that this lymph node receives antigens not only from the form of the parasite injected by the mosquito but also from its intracellular forms, meaning that a full immune reaction is established there. This reaction can therefore be monitored in the skin and the draining lymph node, much more easily than in the liver, in particular to study the action and efficacy of possible vaccine strategies.

The scientists are now working to develop this research in “human” conditions, in other words with parasites infecting humans and “humanized” mice, on which human skin has been grafted.

_______

(1) see our press release (september 1st, 2006)

Picture: In red, keratinocytes (cells in the epidermis), with the nucleus shown in blue. The parasite (green) resides near the hollow formed by the hair follicle, shown in a darker color. © P. Gueirard/Institut Pasteur

Source

Development of the malaria parasite in the skin of the mammalian host, PNAS, 4 octobre 2010.

Pascale Gueirard (1), Joana Tavares (1), Sabine Thiberge (1), Florence Bernex (2), Tomoko Ishino (1,5), Genevieve Milon (3), Blandine Franke-Fayard (4), Chris J. Janse (4), Robert Ménard (1) & Rogerio Amino (1).

(1) Institut Pasteur, Malaria Biology and Genetics Unit, 75724 Paris cedex 15, France

(2) INRA, UMR955 Functional and Medical Genetics and Pathological Anatomy Unit, Ecole Nationale Vétérinaire d'Alfort, Maisons-Alfort, France

(3) Institut Pasteur, Immunophysiology and Intracellular Parasitism Unit, 75724 Paris cedex 15, France

(4) Department of Parasitology, Centre of Infectious Diseases, Leiden University Medical Centre, Leiden, The Netherlands

(5) Current address: Ehime University, Graduate School of Medicine, Department of Molecular Parasitology, Shitsukawa, Toon, Ehime 7910-0295 Japan.

Contact

Institut Pasteur Press Office

Marion Doucet - +33 (0)1 45 68 89 28 - marion.doucet@pasteur.fr

Nadine Peyrolo - +33 (0)1 45 68 81 47 - nadine.peyrolo@pasteur.fr