What are the causes?

The disease is caused by Leishmania parasites which contaminate an insect vector, the sandfly. Around 90 sandfly species transmit these parasites.

How is the parasite transmitted?

Leishmania parasites that are responsible for leishmaniasis are transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected female sandfly.

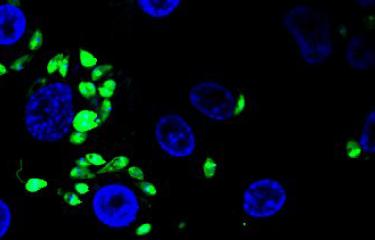

The parasites are injected by sandflies into the mammal host (including humans) in the promastigote stage, i.e. when they have a flagellum. In the dermis, they are captured by macrophages and transform into "amastigotes" (an intracellular stage in which they have no flagellum).

They may subsequently be hosted by cells in different tissues or organs and cause various symptoms characteristic of the disease, depending on factors specific to the host and the Leishmania species.

What are the symptoms?

There are several clinical forms of leishmaniasis, which are broadly classified into different categories.

- Cutaneous leishmaniasis, the most frequent form, is generally benign and is characterized by ulcerated and sometimes crusted lesions, which may occur in very high numbers. The lesions affect uncovered parts of the body and generally heal spontaneously, although they sometimes leave scars.

- Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: depending on the parasite species, cutaneous leishmaniasis may progress to a mucocutaneous or diffuse cutaneous form. This form of leishmaniasis is characterized by destruction of the mucous membranes in the mouth, nose and throat.

- Visceral leishmaniasis is the most severe form of the disease, with symptoms including fever, anemia, weight loss, and swelling of the liver, spleen and lymph nodes. It is fatal if left untreated.

How is leishmaniasis diagnosed?

The various forms of leishmaniasis are diagnosed based on a clinical examination with observation of clinical signs followed by testing for parasites. Serological assays can be performed for visceral leishmaniasis.

What treatments are available?

No vaccines or prophylactic drugs are currently available. WHO and French experts recommend a therapeutic approach addressing the various clinical and parasitological aspects of the disease, which leads to recovery in the vast majority of cases (see the technical report on controlling leishmaniasis).

How can leishmaniasis be prevented?

No vaccines or prophylactic/preventive drugs are currently available.

Early treatment can reduce the prevalence and spread of the disease.

Who is affected?

Leishmaniasis affects impoverished populations. Malnutrition, unsanitary conditions and population movements are the main risk factors.

In 2018, visceral leishmaniasis was endemic in 92 countries, and cutaneous leishmaniasis in 83 countries. Over a billion people currently live in endemic areas and are at risk of developing the disease.

In mainland France, leishmaniasis (mainly visceral) is found in the Cévennes, Côte d'Azur, Corsica, Provence and the Eastern Pyrenees. The parasite species responsible is Leishmania infantum, which also causes canine leishmaniasis. Travelers may also be infected with other species when traveling to endemic countries.

September 2024