As a first-line laboratory in the event of a health emergency, the Pasteur Center in Cameroon was naturally designated as a COVID-19 reference laboratory by the Cameroon health authorities in 2020. How did the Pasteur Center in Cameroon organize its response to this emerging novel virus at national level throughout the epidemic, and how is it monitoring the virus today?

At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Pasteur Center in Cameroon was mandated by the Cameroon Ministry of Public Health to establish and decentralize molecular diagnostics (RT-PCR) for SARS-CoV-2.

With emergency funding from the French Development Agency (AFD), the Pasteur Center in Cameroon was able to mobilize and train up additional staff and also to acquire equipment, reagents and consumables to deal with the high numbers of samples. At regional level, the Institut Pasteur de Dakar, in its mission as a COVID-19 reference laboratory for the World Health Organization (WHO), worked with the Pasteur Center in Cameroon to train staff, perform quality control and sequence the first cases, which was crucial at the start of the outbreak to help them prepare and respond to the pandemic.

Scaling up virological surveillance to shed light on the impact of the novel virus

Decentralization to peripheral laboratories was essential to gain a more detailed understanding of the epidemic. A total of 17 laboratories located in 9 of the country's 10 regions were identified and provided with training and equipment to perform molecular diagnostics for COVID-19. To this end, a questionnaire was sent out in advance to the potential laboratories. On-site visits were then conducted to verify the biosafety level and the availability of molecular biology equipment. Experts from the Pasteur Center in Cameroon subsequently organized on-site cascade training in molecular diagnostics for COVID-19.

To monitor how the virus was circulating in these nine regions, the laboratories in the network also had to be provided with IT equipment and an internet connection. Using data-sharing software developed by the Pasteur Center in Cameroon, the 17 laboratories were able to share their data centrally in real time throughout the epidemic.

"In Cameroon, the situation regarding the COVID-19 epidemic is identical to that in the other countries in Sub-Saharan Africa: the number of confirmed cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection is low, but this is probably an under-estimation," explains Prof. Richard Njouom, Head of the Virology Department.

To gain a better idea of the impact of the pandemic and monitor the development of SARS-CoV-2 on the African continent, the Pasteur Center in Cameroon is taking part in the collaborative research program REPAIR, launched with all the African member institutes in the Pasteur Network.

Developing a better understanding of SARS-CoV-2 circulation

The research carried out in connection with the REPAIR program (International Pasteurian Research Program in Response to Coronavirus in Africa) touches on a variety of fields, including the development and evaluation of diagnostic tests, molecular epidemiology studies of the virus and mathematical modeling of its spread.

"At the Pasteur Center in Cameroon, we developed a colorimetric LAMP assay that is easy to use in the field. The assay is currently under evaluation in Cameroon and in the other REPAIR project partner countries," says Prof. Richard Njouom. "By developing an extensive network for COVID-19 molecular diagnostics, through decentralization and the development of easy-to-use rapid diagnostic tests, we were able to focus on monitoring variants that arrived in the country."

Sequencing, a key tool for monitoring variants

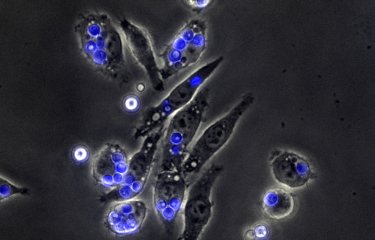

Sequencing is currently an essential technique for studying the spread of SARS-CoV-2 over time and space and pinpointing the emergence of potentially dangerous variants. But this technique requires additional equipment and also staff with training in biotechnology, which excludes many laboratories. When variants began to emerge in 2021, the Pasteur Center in Cameroon enjoyed the support of the Institut Pasteur de Dakar, which sequenced all the samples sent. But the time lag between sending samples and receiving results prevented the center from being sufficiently responsive as the epidemic was developing. The Institut Pasteur in Paris equipped the virology laboratory with a MinION sequencer which could be used to analyze the viral genome.

"This enabled us to introduce genomic monitoring in January 2021, which led to the sequencing of 116 whole genomes and approximately 800 partial sequences of SARS-CoV-2. The results we obtained confirmed the circulation of the Alpha, Beta and Delta variants and very recently the Omicron variant in the country," reports Prof. Richard Njouom.

The MinION is very easy to use but cannot sequence large numbers of genomes. That was where AFROSCREEN came in, a project that aims to strengthen the SARS-CoV-2 genome sequencing capabilities of 25 laboratories in 13 Sub-Saharan African countries. AFROSCREEN will involve new equipment including an Illumina sequencer, training, and epidemiology and public health studies.

"We hope that the AFROSCREEN network will enable us to ramp up our sequencing effort. The other advantage of being part of such a large network, with laboratories in 13 African countries, is the opportunity to share knowledge and data," explains Prof. Njouom. "The Pasteur Center in Cameroon has deposited approximately 200 SARS-CoV-2 nucleotide sequences circulating in Cameroon in the GISAID open-access database, making it possible for the entire international scientific community to monitor and gain a better insight into how the virus is circulating in the region."

Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater

Diagnostics and sequencing based on human populations provides an imperfect picture of the real dynamics of COVID-19 infection, which is why modeling is so important to obtain predictions and anticipate new waves. But this modeling capability is still lacking in many developing countries.

Alternative epidemiological approaches therefore need to be developed. Searching for SARS-CoV-2 and its variants in wastewater could generate additional reliable data and provide a warning signal ahead of an actual wave of infection.

To this end, the Pasteur Center in Cameroon, which already monitors the polio virus in wastewater, is involved in the new project "Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater," funded by the AFD. The project, coordinated by the Institut Pasteur in Paris in partnership with the Obépine network, will be launched in developing countries in the first half of 2022.

The project will begin with a design and preparation phase, with scientific outreach and exchanges between experts and institutions in the countries (to date, 11 countries have expressed an interest in taking part). A second operational rollout phase for wastewater monitoring will then be implemented in a smaller number of countries that satisfy the conditions identified in phase 1.

"Monitoring SARS-CoV-2 in wastewater will enable us to model virus circulation. Since we have fallen behind in vaccinating the population, it is vital for us to be able to alert the health authorities in advance of an outbreak so that they can impose more effective temporary preventive measures," concludes Prof. Richard Njouom.