What are the causes?

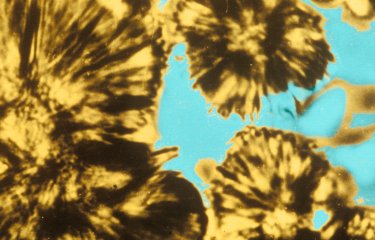

Diphtheria, from the Greek word for "leather" (describing the appearance of the pseudomembrane that forms in patients), is an infection caused by a bacterium of the Corynebacterium genus. Some strains of these bacterial species carry the tox gene (that encodes the diphtheria toxin) and are able to produce diphtheria toxin, causing significant damage to certain organs such as the heart and peripheral nerves (leading to paralysis).

How do the bacteria spread?

Diphtheria is mainly spread through the inhalation of respiratory droplets expelled when infected individuals cough or sneeze. The disease can also be spread through direct contact with contaminated objects or fabric. Once established, the bacteria can produce toxins that damage body tissue.

Infection with C. ulcerans is transmitted by coming into contact with pets, especially dogs or cats, which themselves are often asymptomatic. Human-to-human transmission has never been demonstrated for cases of infection with C. ulcerans.

Infection with C. pseudotuberculosis is very rare and is usually caused by contact with small ruminants, in most cases goats and sheep.

What are the symptoms?

The incubation period for diphtheria is generally between 2 and 5 days. Typical symptoms include a sore throat, fever and a swollen neck. Respiratory diphtheria, the most common form of the disease, is characterized by sore throat, fever, a swollen neck and headache. The very rare cases of infection by C. pseudotuberculosis particularly attack the lymph nodes (necrotizing lymphadenitis).

The typical manifestation of diphtheria is an infection of the upper respiratory tract which can result in paralysis of the central nervous system or of the diaphragm and throat, leading to death by suffocation. C. diphtheriae infection is highly contagious.

How is the disease diagnosed?

A clinical examination and bacterial cultures from throat samples are used to diagnose diphtheria. The diagnosis should be confirmed by tests to detect the toxin, which are carried out at the National Reference Center at the Institut Pasteur.

What treatments are available?

The standard treatment for diphtheria involves administering an antitoxin and/or a course of antibiotics as soon as possible. In addition to this, antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin is recommended, or therapy with macrolides if the patient is allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics. More information is available on the website of the National Reference Center (CNR) for Corynebacteria of the Diphtheriae Complex (in French) and in the guidelines published by the French High Council for Public Health (HCSP) on how to deal with a case of diphtheria.

How can the disease be prevented?

The diphtheria vaccine is the only way of controlling this severe infection. The diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, hepatitis B, poliomyelitis and Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine (abbreviated to DTaP/IPV/Hib/HepB) is a combined vaccine offered to infants. The diphtheria component of the vaccine is composed of purified, inactivated diphtheria toxin. Vaccination is compulsory for all children and healthcare professionals. Primary vaccination is now compulsory for infants at the age of 2 and 4 months. The first booster is given at 11 months and further boosters are given at ages 6, 11-13, 25, 45 and 65, then every 10 years. Seroprevalence studies indicate that a high proportion of individuals aged 50 or over in France have an antibody titer that is undetectable or under the level considered to offer protection. These data emphasize the importance of following vaccine recommendations, especially boosters every 10 years in adults over the age of 65.

How many people are affected?

Surveillance of diphtheria in France is based on the obligation to report all cases. Good vaccination coverage has brought the disease under control in France.

Between 2011 and 2020, 69 cases of infection by C. diphtheriae strains carrying the tox gene were observed. All were either imported cases or cases detected in overseas France, in subjects who had been only partially vaccinated or not vaccinated at all. Most cases were cutaneous diphtheria. None of the patients died.

During the same period, 84 cases of infection with C. ulcerans strains carrying the tox gene were reported in mainland France. The majority were cutaneous diphtheria cases, and unlike the cases caused by C. diphtheriae, some of these patients died from their infections. A common feature of the C. ulcerans infections was that the patients had come into contact with pets, which in many cases were cats and dogs.

The World Health Organization states that morbidity varies by region and according to local public health conditions.

For further details about diphtheria and how to manage it, please consult the following:

- World Health Organization (WHO): Diphtheria

- Santé publique France: Diphtheria surveillance (in French)

- European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC): Information on diphtheria

October 2024